You might have noticed, we talk about Rust a lot. Mostly in the context of embedded programming. However, we also have a few bits and pieces in the cloud side of things. If you have a device that gathers data, you might want to send that data somewhere for further processing and storage. Now, if we are using Rust to implement the embedded side, why not use it on the backend as well?

Sure, why not?

That is mostly how it started. You have a new programming language, you learned a few new tricks, and you really like how it works. So when it came to start some backend development, why not simply try Rust and see where that leads. Worst case, you learned a bit more about Rust in general.

My personal background is Java, and before that C and C++. Using C/C++ you are really in control of performance and resource consumption. However, that comes with a downside, called "undefined behavior" (actually it comes with a bunch of downsides). In a nutshell: your application is fast and efficient, but crashes every now and then, due to a memory corruption you don't know the origin of. Java on the other hand doesn't suffer from that problem, but the Java virtual machine and its garbage collector consume their share of resources.

When it comes to C/C++ vs Java, you trade software engineering time vs compute resources. Writing C/C++ takes as lot more time, but yields (in most cases) more efficient applications. Writing Java code takes less time, but consumes more compute resources when running. The story is similar with other languages like Python, Go, or .NET, whenever a VM or garbage collector comes into play.

So let's see what Rust brings us in the context of frontend and backend. I will not write too much about he embedded side here, as I think we have good posts covering that topic already.

The backend

Backend application are mostly "classic", non-UI applications. The Rust ecosystem has a stockpile of libraries

available to help you implement a server side, networking application. This is also where the async/await keyword

and functionality of Rust comes in handy. So many operations in the backend are of the pattern: wait for request, evaluate,

send request, wait for the outcome, respond to original request.

Asynchronous & efficiency

If you did this all synchronously, waiting for every step, you will have a lot of blocked threads, wasting resources. That is why on the Java side, frameworks like Eclipse Vert.x are so popular now. However, asynchronous Java still feels a bit strange:

private void handleAddCuteName(RoutingContext rc) {

HttpServerResponse response = rc.response();

JsonObject bodyAsJson = rc.getBodyAsJson();

if (bodyAsJson != null && bodyAsJson.containsKey("name")) {

String id = id();

defaultCache.putAsync(bodyAsJson, bodyAsJson.getString("name"))

.thenAccept(s -> {

response

.setStatusCode(201)

.end("Cute name added");

});

} else {

response

.setStatusCode(400)

.end(String.format("Body is %s. 'id' and 'name' should be provided", bodyAsJson));

}

}

Yes, that is due to the fact that Java doesn't see asynchronous programming as concept of the language. It was added "on top" at a later time. And that example is actually rather simple. These nested structures can get out of hand pretty quickly, and make your code hard to understand, and with that it makes it hard to find bugs.

A more understandable way of coding Java is this:

@Path("/country")

public class CountriesResource {

@Inject @RestClient

CountriesService countriesService;

@GET @Path("/name/{name}")

public Set<Country> name(@PathParam String name) {

return countriesService.getByName(name);

}

}

While it is easier to read and understand, it has some downsides: First of all, it is blocking code. A call to name

will only return once the call to the service has returned. Second, annotations and injection are runtime concepts.

That means, that it is processed while the application is running. Although that setup may never change after

the program was compiled, it still consumes resources during runtime. True, Quarkus

does a great job, reducing that overhead, but not fully.

Now lets take a look at a possible Rust variant of that, for example using Actix:

#[get("/")]

async fn index(client: web::Data<Client>) -> HttpResponse {

let result = client.get_result().await?;

HttpResponse::Ok().json(result)

}

That is easy to understand and if you would drill down into the implementation, you would also see that it is quite

efficient. The #[get] attribute (annotation) is actually processed during compile time, creating code on the fly

to wire this up. Alongside that, the async/await keywords

help you write code in a way that the developer can understand, yet the compiler can optimize into an asynchronous

execution flow.

Staying safe

All of that asynchronism is great, but feels a bit dangerous, when you come from a Java or C/C++ world. Multiple threads, passing along of data structures and states, all in a network application context. Don't forget that Rust has all kinds of features to help out, tracking ownership of data and ensuring that data can safely be shared in a concurrent environment.

You get the best of both worlds.

The frontend

Having a backend API is great, but as important as that is a decent web UI. Sometimes you just want to push a few

buttons and don't want to craft up the required curl command for the server to accept your request.

What was and might be

Personally I am allergic to JavaScript. HTML and CSS is ok, but I never could learn to live with the quirks and pitfalls of JavaScript. While you have lots of alternatives outside the browser, inside you just had to use it.

Yes, had! Now we have a thing called WASM.

Just putting aside all my dislike for JavaScript for the moment, here is a good reason for considering WASM. I would recommend watching the full talk. Additionally to the other benefits of Rust, switching to WASM improved the performance over 3 times.

Rust and WASM

Rust has great support for WASM. Not only the compiler, or a set of libraries, which interface with the browser APIs. Using the Yew project, you can create complete front-end web applications, like ReactJS. Yew itself doesn't provide you any components out of the box, but there is for example, a project called ybc, which allows you to use Bulma (a project similar to boostrap) as part of Yew.

While Bulma is a great framework, PatternFly seems to be a better fit for a more dashboardy, console-ish web application like ours. So here you go: PatternFly for Yew.

All shiny?

Not everything. Actix had a few troubles in the past with their community. The recent upgrade of Tokio to version 1 (which is a breaking change) might cause some ripples in your dependency tree. Some libraries exist in Java that you miss in Rust. Then again, nothing that other ecosystems don't see as well.

Also does the typical experience of Rust prevail in frontend, backend, and embedded: you need to sit down with your compiler and have a decent review of your code. In the end the compiler will convince you that your code is full of bugs, you come back with a better version. Once it compiles, it runs! That process, of finding bugs/issues early in the process, might cause some frustration.

What are the benefits

There is a lot of good stuff that comes out of it though.

Sane frontends

First of all, JavaScript is mostly gone. All the features like type safety, ownership, exhaustive match patterns, are finally available in the frontend as well. Just as an example, the following code is from our console. We have some app page routing, using an enum, and some code to render the main content, using the router switch:

pub enum AppRoute {

#[to = "/spy"]

Spy,

#[to = "/examples"]

Examples,

#[to = "/"]

Index,

}

fn content() -> Html {

html!{

<Router<AppRoute, ()>

redirect = Router::redirect(|_|AppRoute::Index)

render = Router::render(|switch: AppRoute| {

match switch {

AppRoute::Spy => html!{<Spy/>},

AppRoute::Index => html!{<Index/>},

AppRoute::Examples => html!{<Examples/>},

}

})

/>

}

}

Adding a new variant to the enum, will automatically trigger a compiler error, since the match in the router is

no longer exhaustive. You simply can't forget to handle it.

Different worlds, same language

No matter if you are programming embedded, backend, or frontend, you always use the same language. Not only can you re-use your knowledge about the programming language, but also data structures and even logic. Test and document it in the same way.

I mentioned earlier that inside the browser you only had JavaScript as an option. Not entirely true. We also had Java and .NET applets, and there was Flash. The same for the embedded side: there was JavaME for microcontrollers, there still is Micropython and a few others.

However, with Rust, you now have the ability to really use the same technology in all three areas. Not just as "plug-in", like Java applets, or a VM like Micropython. It doesn't require a garbage collector on an embedded device, and can even revert to static memory allocation, if you wish to do that. None of the other languages is able to achieve that.

None? Really?

True, C and C++ can run on frontend, backend, and embedded as well. Achieving similar performance, while not requiring garbage collection.

However, coming back to the original problem, writing working/bug-free C/C++ code is much more time-consuming than writing the same code in Rust. Rust prevents you from many programming errors already during compile time. That benefit in development speed, also results in more functionality being created. People can solve more issues in their time, which automatically results in more open source dependencies you can leverage for your own project.

Also, did you try out cargo embed? Within a few minutes you are up and running, flashing your device. Setting up a

complete C/C++ toolchain for embedded devices takes way longer. Even when using projects like Platform.io or Arduino.

Which means that you can also re-use the same dependency manager and build tool for all of your projects.

Conclusion

I am pretty sure that we wouldn't have achieved that much in our time if we had worked with C/C++ on the backend and frontend side. Using JavaScript on the frontend, allergies aside, would have required to use three different languages and ecosystems.

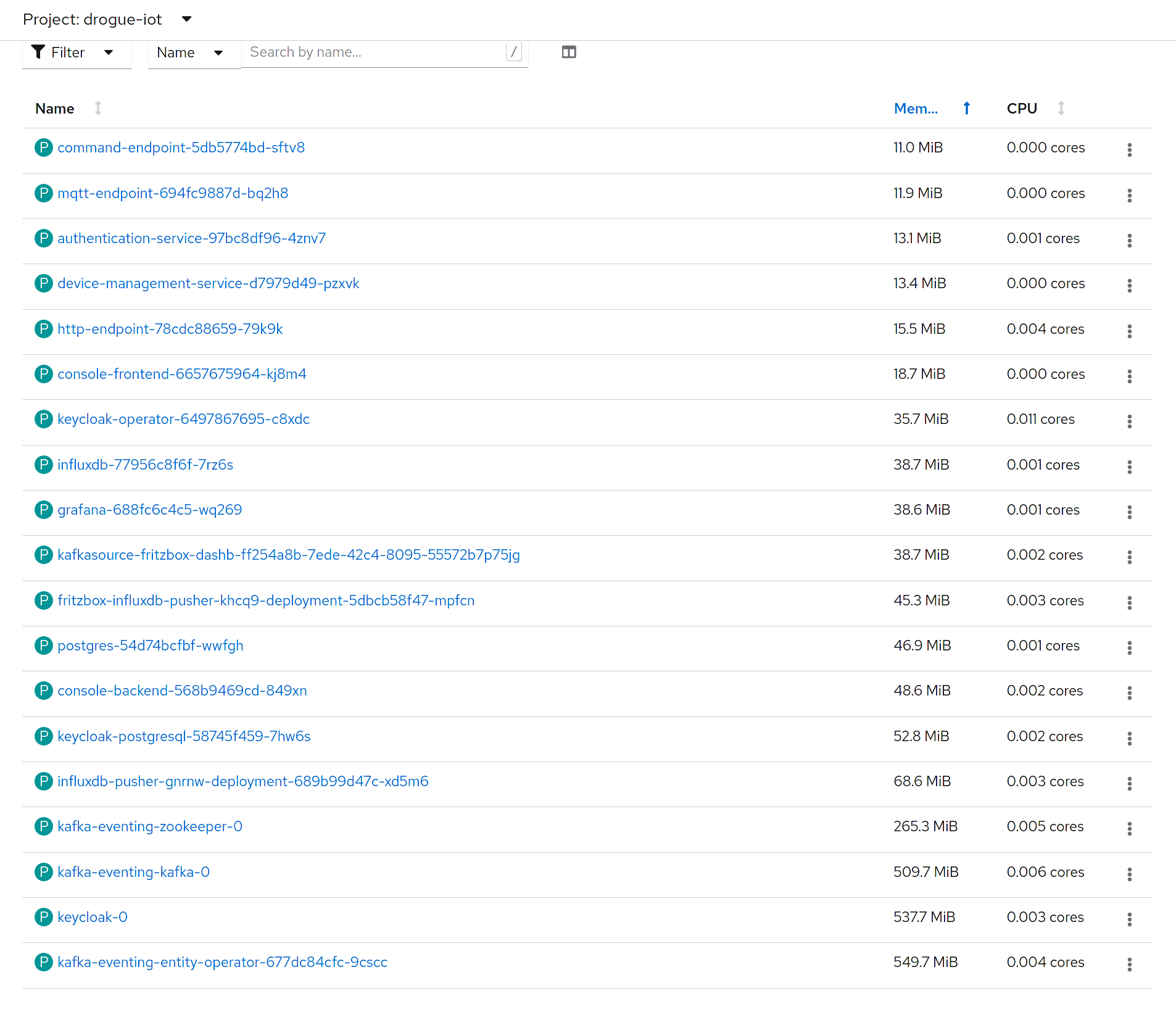

Using Java would have been an option, but I will leave you with a screenshot of my cluster, running Drogue IoT cloud. You will see the pods, sorted by memory consumption. Try to figure out which processes are written in Rust, in Go, or in Java.